Home » Articles posted by Terence Clarke (Page 11)

Author Archives: Terence Clarke

OMG!@e-speak

In the history of literature, the genre of the letter has been a very important element. Epistolary exchange has shed light on the lives of most of the important artists and historical figures — and some less important figures that happened to have written well — in the history of the world.

This light has revealed profound emotional difficulty and expressions of love… savored love, questioned love and destroyed love. Letters often exposed the high comedy of family disputes. The horrors of war were made memorable in letters from the front, while the onerous effects of preposterous government or church intrusion on the sensuous spirit were brought into the open. The letter, as a form, shed clear light on just about everything.

Now we have email. When I first encountered this phenomenon several years ago, I was heartened. With the birth of the telephone and, much later, the television, good personal writing had abruptly disappeared. It was easier to pick up the phone and call. It was more fulfilling to watch a game show than to write to your lover. So, most people gave up writing letters, and an entire literary genre almost ceased to exist.

Email held out the possibility for a resurgence of the letter-form through use of the Internet. Perhaps now people would write to one another again, a consummation devoutly to be wished. The letter is so important to the history of human affairs that its disappearance was like the withering away of a human organ, one that spirits the blood and makes it flow. Email would restore that organ, I hoped.

It has become apparent, though, that email has not risen to the challenge.

Letters hold together. Emails often have nothing to grab on to. Letters call for contemplation and soulful enjoyment. Emails call for very little. Letters contain cries for understanding, personal descriptions of terrible events or recoveries of soul. Emails tap-tap-tap across a depthless surface, asking only that they not be ignored, which they so often are. Letters contain a beginning, a middle and an end. Emails are dull wisps of nothing, written in as few characters as possible. It is this kind of artless dodging of anything important that is the norm in email and in its little brother, texting. And texting’s little brother, the tweet, is now the perfect email.

So my wish for the return of real writing has not been fulfilled. This is due to something I had not foreseen at all, which is that although the usual emailer may want exchange of some kind (perhaps a revised bill of lading, a recipe for goulash or Miley Cyrus’s URL), an email generally is not exchange. It almost never cares for good writing. The email is a depthless, short, ungrammatical demand. There are slightly meaningful emails, to be sure, like those that talk about one’s cat or how to screw in a light bulb. But even emails like these are random momentary conversations that go nowhere, or at least not far.

And now, horror of horrors, we have the Twitter novel, which somehow I feel is not destined — at least yet — to deny Dickens and all those others their insurmountable place in the pantheon. But it might. We will have seen the end of human transcendence on this planet when a chapter like number 42 in Moby Dick, on the whiteness of the whale, which is surely one of the most lyric and strange pieces of writing in the English language, is replaced by a chapter of 140 characters that have little to do with each other, as is the case with most tweets.

So, for the vast majority of this new language I propose the term “@e-speak.” The word could be an adjective, a kind of descriptive term that refers simply to the nature of the email/tweet itself. For example, you read a short little tweet, of a few impenetrable words and signs, with no capital letters and no punctuation, something about nothing written in illiterate language. It rattles with @e-speak inconsequence. That’s an adjective.

My use of the term would also make it into a noun. @e-speak is the language that, in another context, would be called gibberish. OMG!

Terence Clarke’s New York story “Everyone in L.A.” is available at Amazon.com. Visit him on Twitter…

Silence

The new rudeness is silence.

I first became aware of this during the dot.com bust of 2000, when I was working as a marketing executive for an Internet software startup in San Francisco. This was one of those companies, still very much in evidence, that was run by men under thirty-years-old whose background was in the computer sciences and the Internet. They worked eighty-hour weeks regularly. Their favorite cuisine was cold pizza washed down with warm Coke, and they were barely capable of spoken language. They dressed like skateboarders.

Few had any manners. The founder and CEO of the company for which I was working — as a marketing executive responsible for selling the product to Fortune 500 companies — was a young German who had cut his business teeth in Silicon Valley, at one of the very large computer equipment companies. He had no personality, but he had invented what appeared to me to be a very good software product. The trouble was that his rudeness, characterized by his silence in response to the pesky questions of employees, and his silence during sales or marketing presentations to clients, added tremendous weight to the effort to sell the product. Marketing and sales, he sniffed — silently — were beneath him.

Many such have made millions in their start-up business endeavors, and I, who had devoted a career to working in corporations, was smitten with the idea of stock options and the probable millions that I would make too. So, putting my suits and neckties in the closet, I too took to Levis, although I drew the line at warm Coke.

I retained one other habit that I could not shake. I had good manners.

I always returned phone calls. I was considerate of my clients and their real wishes. I did not bully people in order to make the sale. When I emailed someone, I used full sentences, full words, full thoughts. Above all, when asked for an opinion, I gave it, expecting that, since my opinion was being sought, it would be considered.

But I often felt that my manners rendered me beneath contempt by those who ran this company. I was considered old-fashioned, too genteel for my own good, and not decisive enough. My manners were responded to with impatient silence, as though I would never, ever get to the point.

I left that company, the last I ever worked for, six months before it went under to the tune of sixteen million dollars in venture capital investment. The CEO left for New Zealand the day after the failure, I expect silently, and as far as I know has not visited the United States since.

Once I left business myself — in order to write full time — I figured that this new rudeness would also be left behind. But no. I’ve come to understand a subtle variant of the new rudeness, which is not based on the need for business dominance, but rather is being accepted in social circles as the new way of being polite.

Here are a few instances… You issue an invitation to friends to join you for a weekend in the mountains, and they simply don’t respond. You leave a voicemail asking someone to call you back, and he doesn’t. So you ask again, and he doesn’t, again. A long-term friend no longer returns your voicemails, and will give no explanation for why, other than a friendly avowal that there’s nothing wrong at all, followed by continuing long silence. Or your friends email you, inviting you for a weekend in the mountains, and you respond right away that you’d love to join them, “What can I bring?” etc., etc., and there is no more information offered. The invitation is forgotten or ignored by the people who issued it, and the matter is never brought up again.

It’s the worst when the silence is hidden behind a veil of smiling good will. You’ve called someone for an answer that you both realize you really need, to a question that you’ve left for that person in emails and voicemails many times, and when she picks up the phone, she regales you with patronizing good humor and the thought that you’ve been on her mind many times recently. Then, as a kindly afterthought, she hurries to the answer to your question. With regard to your many unanswered messages, there is only silence.

Everyone acts as though there never was such a relationship, never such invitations, never such questions. Silence reigns, the good manners that would enable a forthright conversation go out the window, and we arrive at the very summit of the new rudeness.

More silence.

No response is not enough. The 18th century British statesman Lord Chesterfield wrote that “manners must adorn knowledge, and smooth its way through the world.” I doubt that there are many in the United States now who would understand what Chesterfield was even talking about.

(This piece first appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle.)

Saddle Up! And Don’t Forget Your Hat.

Until recently, I never myself owned a cowboy hat. Then I met Jimmy Harrison.

I have envied many cowboy hats in my life. John Wayne’s, for instance, which is iconically famous, a big hat for a big man, its very wide brim reminding me of a ship’s wake making its way across a troubled sea. Clint Eastwood’s is not as grand, but it very much suggests the character that he plays in the spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone. The hat is grizzled and slow to burn. It says little. Its crown resembles a dented tin can that its owner has carried around from one gunfight to the next.

Then there is Noah Beery Jr.’s. A lot of people may not remember him, a character actor who played in many westerns from the thirties to the fifties and went on to a career on television’s Rockford Files as James Garner’s father. He is one of my favorite screen cowpokes, principally because of his hat. It resembles a porkpie, its narrow brim rolled up all the way around. He wears the hat back on his head, a shock of hair coming out from beneath it to adorn his forehead. In Red River, one of John Wayne’s greatest films, Beery’s character, Buster McGee, is always identifiable because of this hat, which is totally unique among those of all the other cowboys in the movie. Even in the famous roundup scene that begins with the cowpunchers whooping it up individually, each one singled out by the camera through almost a dozen cameo close-ups, Beery’s is special because the hat makes him look like a little kid hurrying to play cowboy. He’s excited, happy and ready to ride.

Then, in the chaotic scene filled with long shots in which the cattle are, indeed, being rounded up by all the cowboys, you can identify Beery immediately because of his hat. Horses are flying around. Cattle are confused and afraid. Dust is everywhere. Beery on his horse battles all these elements, his hat consistently reminding you of exactly which cowpoke he is.

Jimmy Harrison is the founder and proprietor of Double H Custom Hat Company

in Darby, Montana, and among those who know their hats, he is a famous man. He has built hats — his phrase — for Dick Butkus, Willie Nelson, Garth Brooks, Emmylou Harris, chef Paul Prudhomme and former Mayor Willie Brown of San Francisco, among many thousands of other customers.

Jimmy operates out of his store in downtown Darby, a town of perhaps a thousand people at the southern end of Montana’s Bitterroot Valley. He builds several lines of hats that he displays in the shop, but his favorites—and his most popular—are those he custom builds for individual clients. The workroom behind his store is a place filled with hundreds of remnants of felt and leather, hand tools, work tables, hat forms, hand-made hat bands, photographs of Jimmy, his family, friends and customers, all in a seeming jumble of confusion. But it is also a place where careful thought, individual pride, precise handiwork, thoughtful design and only the best of materials come together in each individual hat. “I guarantee everything,” he says. “You can wear these hats forever.”

My fitting for a Double H hat took about twenty minutes. Jimmy sat me down on a stool in the shop and brought out a metal device that he fitted over my head. It was a kind of airy helmet. One circular piece of thin, pliant metal went around my head horizontally. It was connected to a few pieces of the same metal that fit over the top of my head, front to back and side to side. There were bolt-like adjusters that tightened or loosened the whole device as Jimmy set about figuring out the exact outside dimensions of my skull.

He took many notes. As he carefully adjusted the device, I felt that I was being examined by a nineteenth century physiognomist to determine the nature of my inner being, my character and the level of my intelligence. I also briefly felt as though I were being readied for the electric chair. But finally Jimmy was satisfied, and he told me there would be no problem building a hat that I would truly value. It came to my office in San Francisco about six weeks later, and fit perfectly.

Among hat makers, Jimmy is a purest. “I guarantee everything,” he says. “I put the ‘HH’ brand on every hat I make, and that means it’s the highest quality. The materials in my hats are simple. The prime quality is a 100 percent beaver felt, and I also make a less expensive model with a 50-50 mixture of beaver and rabbit felt.” He removes his own, a black cowboy hat that appears to be in perfect shape, brand new. “This one’s 15 years old. 100 percent beaver. It still holds its shape perfectly. It blocks very well, and I wash it once a year. So it’s been washed 15 times.” He holds it out before him for inspection. It still looks pristine. “You’re not going to get a hat like this somewhere else.”

Making these hats is not Jimmy’s only talent. As a very young man, he rode steers and horses in the rodeo. This was tough duty. “It wasn’t the same then as it is now. Now you’ve got all this money and big prizes. When I was doing it, it was for the fun of it. The skill. You’d take a fall. You’d get back up. You know, I’d make a couple hundred dollars a year and think that was great.”

But there was a price to be paid. Once, while riding a bronco, Jimmy was thrown to the ground with such force that he broke his pelvis in several places. “Yeah, it had to be knitted back up again.” Jimmy took it pretty much in stride, but decided that another line of work was in order. “But there weren’t a lot of physical jobs I could do, and I really enjoy working with my hands.” Jimmy had already been learning about shaping hats, and he saw that he had a distinct talent for this sort of thing, “Building a hat appealed to me. It’s a tangible product, and you can see that you’ve done something.”

So he apprenticed himself to Sheila Kirkpatrick, a custom hat maker in Wisdom, Montana. He had known her for years, and had heard that she was going to sell her business. He asked if he could learn the basics from her, and with that he set about mastering the art. “And I’ve done pretty good,” Jimmy smiles.

Incidentally, Jimmy shrugs at the idea that rodeo was a very dangerous thing to be doing. “I worked as a cowboy for some years, too. And I think I probably got more injuries from that than from riding those broncos.”

“One of the hardest hats to make,” Jimmy says, “is an old beat up one. Someone will bring in his grandfather’s hat, that looks like it’s been out in the backyard in heavy weather for years. It’s got big stains. The brim is faded and it’s lost its shape. You know, it looks terrible. But the guy loves it because it was his grandfather’s. So he wants a new one just like it. In just as bad a condition, but a brand new one.” Jimmy shrugs. “That’s very hard to do.” He surveys his shop and all the examples of his artisan craftsmanship. “But that’s part of the game. That’s what they want.”

For Jimmy, the customer is king. “If I make a hat that suits you, it will become part of you. I’ve had people come into the store and the fellow will buy a cowboy hat for his wife, custom-designed, custom-fitted. And when she gets it, she’ll say ‘This is so beautiful, I want to hang it on a wall.’ But you know, a year later, they’ll come back in, and she’ll have the hat on, and her husband will tell me ‘Jimmy, she wears that hat everywhere she goes.'”

He looks around the shop, at the shelves and racks that hold the myriad non-custom hats he has built (nonetheless by hand, nonetheless of top quality) and nods. His own black hat adds unmistakable cachet to the gesture. “My favorite customer? Someone who’s gonna appreciate it. And above all, no one that leaves here with one of my hats is gonna look silly. I make the top quality hat, and people like the fact that I can give them one.”

Terence Clarke’s new novel The Notorious Dream of Jesús Lázaro will be published later this year. This piece appeared originally in Huffington Post.

The Bohemians in San Francisco

If, like me, you live on Russian Hill in San Francisco, or if you care for fine and adventurous writing, Ben Tarnoff’s The Bohemians: Mark Twain and The San Francisco Writers Who Reinvented American Literature is for you. Mark Twain lived and wrote in San Francisco for a few years in the 1860s, and he formed close friendships with a few other writers in this city. San Francisco was far from the action of The Civil War, but was seeing meteoric growth because of it. The Gold Rush had more or less played out, but the city was becoming a manufacturing and shipping hub, and there was an unusual number of newspapers and magazines, all of which needed typesetters and writers.

If, like me, you live on Russian Hill in San Francisco, or if you care for fine and adventurous writing, Ben Tarnoff’s The Bohemians: Mark Twain and The San Francisco Writers Who Reinvented American Literature is for you. Mark Twain lived and wrote in San Francisco for a few years in the 1860s, and he formed close friendships with a few other writers in this city. San Francisco was far from the action of The Civil War, but was seeing meteoric growth because of it. The Gold Rush had more or less played out, but the city was becoming a manufacturing and shipping hub, and there was an unusual number of newspapers and magazines, all of which needed typesetters and writers.

Twain and Bret Harte were men with both these talents, and in San Francisco they formed, with the poets Ina Coolbrith and Charles Warren Stoddard, a literary group that became known as The Bohemians. The West in general, and California (and San Francisco) in particular, were the home of a remarkable literary boom that was fueled principally by these four people. Its signature style – particularly in the work of Twain and Harte – was notable for its use of western slang, a kind of swagger and drawl that at first was more a spoken style than a formal written one. The tall tales of the far west used that slang to great popular amusement. Twain and Harte wrote the finest examples of it…in Twain’s case “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” published in 1865, and in Harte’s “The Luck of Roaring Camp” in 1868. Both men became celebrities, and were lionized nationwide once they were recognized by east coast publishers like William Dean Howells, who held themselves as the arbiters of literary taste in the United States at the time.

Twain’s career went on to become legend, while with time those of the other three writers faded. The Bohemians shows nonetheless that the four of them wrote in ways that opened an entirely new American writing that was freed of the restraints imposed on it by its until-then adherence to straitened European standards of decorum. You could now write about the wilds of America out west, and do it in the language of the west. It was a revolutionary moment in American letters.

Writing about the beginnings of this literary flourish, Tarnoff says this: “The Far West offered a possible path forward. On the frontier, the rudiments of a new kind of writing were beginning to take shape. It would succeed only on its own terms, not by slavish emulation of New England or the wholesale adoption of Atlantic tastes, but by discovering the value of its local materials, by broadening its vision to see what was hiding in plain sight.”

Writers are often pictured as solitary individuals wrestling with their own thoughts in isolation and worry. When they are in the actual act of writing, this is usually true. But as so often happens, the collaborative exchange of ideas and feelings between writers is equally important to what they eventually put on the page. Tarnoff writes with great feeling about the friendship that these four writers shared in rough and tumble San Francisco, and the eventual breakdown of that friendship as Twains’s star rose and those of the others faded. Bret Harte was an invaluable editor to Twain, Stoddard and Coolbrith, while Twain helped his friends with advice, affection and, occasionally, money. Ina Coolbrith’s home on Russian Hill was the scene of many conversations, cups of tea, and the sharing of ideas and inspirations. Emblematic of the affection that these writers had for each other, at least during their time together in San Francisco, is a remark that Ina Coolbrith made to Charles Warren Stoddard: “The friendship between us has been more to me than the love of any man.”

Many other compelling characters figure in this fine book. The wealthy San Francisco society woman Jesse Benton Frémont was instrumental to the beginnings of the Bohemian flowering, as was a Unitarian preacher named Thomas Starr King, a riveting public speaker whose 1864 funeral was attended by 20,000 San Franciscans. Artemus Ward, a famous comedian and best-selling author, was on tour, and befriended Mark Twain in San Francisco. His influence was instrumental to Twain’s own development as a comic writer and, above all, a major public figure.

Terence Clarke’s new novel The Notorious Dream of Jesús Lázaro, about an artist in San Francisco, will be published later this year. This piece first appeared in Huffington Post.

How’s That Novel of Yours Doing?

The wish for fame, so illusory a thing, can kill you. Or at least, it can kill your novel.

The wish for fame, so illusory a thing, can kill you. Or at least, it can kill your novel.

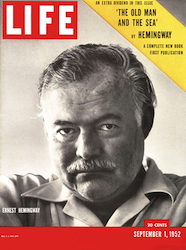

In an essay in The Spectator in 1711, Sir Richard Steele wrote that it is “the worst way in the world to Fame, to be too anxious about it.” For almost all of us who took up writing in order to be like Ernest Hemingway, this is good advice. The Hemingway goal hasn’t worked in my case or, I suspect, in that of most others who have had so markedly specific an intention. Perhaps all others. This is so because such a goal has nothing to do with writing well. It has an awful lot to do with churlish envy, as well as what we know about Hemingway, that he marketed himself almost from the beginning in order to get where he got.

Perhaps his remarkable fame derives from the great interest there has always been in his adventurous life. But I think his adventures had little to do with his ability to write well, as he so often did. In his writing, he sought to please his one greatest fan, which was himself, and for this steadfastness he deserves the congratulation he gets.

When I began writing seriously, I had the theory that writing fiction was a public, not a private, endeavor. Because it is so intense a form of communication, it seemed foolish to me to write without the idea of getting published. Publishing with an established firm, either major or minor, was then the only way of getting your work in front of a public. So, without publishing, there was no communication, and without a public, writing to me wasn’t worth doing.

But then, as now, there was a gauntlet that writers had to run, to get to the golden moment of publication by a major U.S. publisher. Like a great moat surrounding an obdurately faceless castle, the army of literary agents floats about, thick with weeds and goo. Any writer who has spent time in these waters has a library of favorite phrases that he or she has learned from agents. “Your work has significant integrity, but needs to be fleshed out a bit more.” “Though excellent, it’s just not right for us at this time.” “You’re clearly a writer with great promise, and we wish you the best in your search for representation elsewhere.” “Couldn’t possibly sell this in today’s difficult market.” And many more.

The single best one my work ever evoked came from an agent employed by a West Coast firm, both now very long gone. The entirety of his communication to me read, “Wooden, foolish, a little bit trite… But, thanks!”

Until the advent of self-publication on the internet, two-thirds of the manuscripts published in the United States in any given year by major companies were represented by literary agents, and to this day, when you look at the submissions guidelines for most major publishers, they say that they will not consider “unagented” work. So that seems pretty open and shut. If you want to publish with one of the Big Six, you need an agent. Thus you go swimming — because you must — in the moat, an experience that, if you do not have a ribald, very well oiled sense of confident humor, will drive you nuts.

Dealing with the major publishers themselves — should you survive the moat — is much easier because you have a goal, they are demonstrably interested and they know who you are. It’s just you and your editor, and you have a common wish.

There is a second problem with the Hemingway ideal, a problem spelled out succinctly by Richard Steele. If you write to be famous, the quality of your work will almost certainly be damaged by the anxiety with which you’re writing. You have the memory of all those great books, written by writers you admire tremendously, and there comes the time, often, when you worry that what you do will never come up to the level of what they did. You finish writing a paragraph or two, then you recall Joseph Conrad writing about something similar, or Joyce or Greene or Ellison or Dickens or Austen, Eliot, Nabakov, Baldwin, Faulkner… You stop writing. Or you continue on, the shades of all these others standing behind you, dark, celebrated, bookish shades brimming with talent, writers now long dead except for their great fame. You sense them watching what you’re doing.

It doesn’t work, and you won’t make it.

When I finally understood this and backed off, my writing improved and I started getting published. Right away. It was a simple, one-to-one relationship. Now I pay occasional attention to the idea of fame, when I’m reading about Lady Gaga or some such. But I never allow such a thing to affect what I’m doing. Fame is something others bestow upon you. Good writing is what you bestow upon yourself, your own most faithful, loving, and observant fan. If you don’t write for the emotional benefit of that reader, I believe your chances for fame will vanish.