A New Novel…The Guns of Lana’i…and a modest proposal.

The question in the novelist’s mind once he/she thinks it’s ready, is this: What now?

There are still many gates through which to pass: Wander through the medieval gauntlet of literary agents and publishing houses? Or publish it yourself and get on with it? Got to send it to your editor. Got to get it designed. Who does the cover? What about the marketing? Is there a movie in this? Will HBO go for it?

This too is a gauntlet, but one way worth going through. So…I hope you’ll consider assisting my effort by contributing to my GoFundMe account for this new book. You can find it here.

What’s The Guns of Lana’i about? In 1907, Kimo Severance completes a fifteen-year sentence in the Honolulu federal prison for his participation in a failed bank robbery. “Prison had taken the fired anger that had driven him as a boy and slowly, inexorably dampened it, so that now he hoped he could simply set up somewhere.”

With a fellow former convict, an Argentine gaucho named El Pituco, Kimo goes to the Hawaiian island of Lana’i, across the channel from Maui. His wish for personal peace encounters immediate difficulty as he discovers the extent to which the Hawaiians ( the Kānaka Maoli) on the island have been subjugated by its usurping white owner, Tom Morgan.

With the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy by white Americans, Morgan had taken this island as his own. The novel tells of the conflict between the Hawaiian descendants of the former rulers of Lana’i and the ruthless haole owner (i.e. white mainlander). Violent conflict on the island is the result.

This is a story of a disenfranchised people attempting to regain their birthright…with the help of another haole (the ex-con Kimo), and Pituco…sometimes with disastrous results. An important contributing factor to the conflict among the Hawaiians themselves is the love between Kimo and Elizabeth Kailani Alaka’i, the sister of the island’s Hawaiian leader, Junior Alaka’i.

Here is a passage from the book. Anyone who knows the island of Lana’i will recognize the landscape. (If you don’t know the island, get thee hence to the nearest airport.):

“Benito ascended the trail from Kō‘ele toward Keahiakawelo, The Garden of The Gods. Kimo, holding the horse’s reins in one hand, searched for the mud-clogged trail. Because it had rained so heavily the afternoon and night before, the soft grazing lands had been inundated with runoff. Benito’s lower legs were striated with mud. Kimo had had to dismount at one place in the trail, where the trail itself had disappeared into a shallow pond of mud for a quarter of a mile. Brown, red, and black mud had clotted his pants, so that they fit him more like filth-laden slime, weighing more and more as he led Benito to the rise in the ground from which the trail re-emerged.

“The trail followed a steady climb up a ridge, the far northern end of what had survived the disintegration of the Lana’i volcano. It was unclear when this explosion had taken place. Junior had described it as ‘a big one, yeah. Million years ago, maybe. Nobody here when it happened. And for sure…’ He grinned. ‘Nobody here after it happened.’”

“Kimo had always pictured lava fields as black. He had read about them (Von Humboldt on Chimborazo…Fiorelli in Pompeii) imagining their vast obsidian tumblings down mountainsides and slopes in places like Sicily, Greece, and Chile. Smoke rose from them as they would from The Lakes of Perdition, filled with demonic, suffocating fire.

“But he did not understand what the full consequence of such explosions could be until he read The Eruption of Krakatoa, and Subsequent Phenomena, a book written in 1888 by members of The Royal Society of Great Britain. Kimo had just arrived in Los Angeles from Mexico, having read almost nothing in the two years he had spent in that country. He found the book at the public library and, first noting its heft and small print, he was reminded of the books that his father would leave on his desk, unsigned and without a note of any kind. It was expected that the boy would read the books, and soon.

“In the case of this book, sitting at a table in the shaded library building on a July afternoon, he was drawn to read it from the very first page.

“‘The extremely violent nature of the eruption of Krakatoa on August 26th – 27th, 1883, was known in England very shortly after it occurred, but it was not until a month later that the exceptional character of some of the attendant phenomena was reported. Blue and green suns were stated to have been seen in various tropical countries; then came records of peculiar haze; in November the extraordinary twilight glows in the British Isles commanded general attention, and their probable connection with Krakatoa was pointed out by various writers.’

“Kimo read on, about the great death-bearing tsunamis hurtling from the mountainous ruin, the blackened heavens, the barometric waves colliding with one another half a world away, bouncing back upon themselves, ricocheting, colliding again and bouncing back again, and the dead creatures strewn across oceans, what seemed like the end of the world, everywhere in the world.

“Now, this peak on Lana’i, which had been left behind when its own explosion came, was perhaps a quarter of the mountain that had previously existed. So when the mountain had disintegrated, Kimo mused, the blast must have broadcast itself for hundreds of miles directly to the west, south and north across the immensity of the sea itself. The sky would have been blocked out entirely, as it had been at Krakatoa, bludgeoning the air and making it not breathable. Kimo envisioned the tsunami moving so hurriedly beneath this darkness, with such force across the empty sea to whatever unfortunate shores awaited it, the animals on those shores, those threading their way toward becoming human, those that slunk, crawled and slid across the land, even those that attempted to fly from the surge…all destroyed by the arrival of the blistering air, the pumice dust, and the immense waters.

“The Garden of The Gods formed an enormous pebbled runoff of volcanic blast waste and stone. It had been eroded by rain and wind for the million years since the blast, and covered the entirety of the ridge up which Kimo urged Benito.

“‘They say the gods used to dig up these rocks when they gardened the heavens, see?’ Junior had further explained. ‘And tossed them aside down here.’

“Benito passed from the grass slope into the beginnings of the Garden, continuing up the steep ridge. The entry itself was hidden by a few very large boulders ahead, so that the unknowing rider would not be prepared for the immensity of what he was about to see.

“The Garden, swept over by heavy gales, lay tinted in pinks, wine-reds, sea-blues and purples. Sand and boulders were everywhere, some gathered into great, deteriorated moraines, others alone, isolated and somber, a colored moon. Except for the ocean far below, the peak of Mount Lana’ihale to the right, and the islands of Maui and Moloka’i far across the strait, the Garden took up the entire field of view.

“Kimo rode slowly, alone, Benito negotiating the rock-strewn trail. He had traversed the Garden just once before, on the ride over with Junior, Herman Keala, and Pituco. But he knew already that he would seldom be so immersed in such extra-planetary beauty. Solitude here was violent and battered by winds. He had little imagined in prison that such a place as this even existed. Now, shocked by how riveting a beauty the volcano’s destruction had caused, Kimo felt that he was a fresh visitor at the demise of the world.

“Benito rounded a partially crushed blue-purple boulder, and began a climb to a higher plain. Up ahead, another horse stood tethered to a large stone in the middle of a rise of pink and brown sand. Its rider stood next to the horse, adjusting the saddle. The wind scattered her black hair, and her long cotton skirt, also wrapped about her, became free, and then wrapped her again as the winds enveloped her.

“Surprised by the appearance of another rider, she turned and gathered her hair behind her head with both hands, the better to see clearly. She was the one person Kimo could have wished to see here…exposed, free, and alive….Elizabeth.”

The Guns of Lana’i is, by the way, my ninth book of fiction, along with three of non-fiction. For information about them, please click here.

I hope you’ll find this of interest. Once you’ve donated to the cause, you’ll hear from me with a very personal thank you, updates on how it’s publication is going, and more news. Once, again, here’s the GoFundMe.

And please…tell your friends!

© Copyright 2022. Terence Clarke. All rights reserved.

Prolific? What’s That?

February 17, 2021

I have been accused…wrongly…of being prolific. A book a year over the last seven years. Words and more words.

But it’s not true.

One of the curses of writing fiction is that, in general, it does not sell as well as non-fiction. The reasons for that are many and have been written about a great deal (itself another source of non-fiction.) But it is just a plain fact that, as a rule, English-speaking people don’t read nearly enough fiction.

Those of us devoted to writing fiction must accept that fact. But, if the practice compels you as a writer, it doesn’t matter. The wander of mind that fiction requires is for a writer one of its great attractions. The individualism of it. The adventures of the soul and the heart. The challenge of making something up out of whole cloth. It’s fun. Even tragic fiction is fun…to write, if perhaps not to read. You can do what you want with fiction.

But I have to tell the truth. I am hardly prolific.

After the publication by Mercury House and Ballantine Books of my novel My Father In the Night,in 1991 (my third book) I couldn’t get anything published at all. This was during the antediluvian times prior to the internet and the revolution it has caused in book publishing. So, if you were serious as a writer, you had to run the gauntlet of literary agents and the Big Four (or Five or Six, whatever it was depending upon the many corporate takeovers) of serious publishing houses. Each of those two gauntlets represented a very rough passage through which you and your fiction manuscript had to pass. In my case, I would say that I have received favorable reactions from maybe two percent of the hundreds of query letters and subsequent correspondences I have had with literary agents and publishers.

My favorite was a letter and contract I received from one New York agent who wished to represent a novel I had sent her. I was thrilled…except that her contract would seal me into an arrangement from which, if I signed, I would not be allowed to leave were I to be dissatisfied for some reason. (Although she could get rid of me, if she wished, as spelled out in the contract.) Also, the agent required that I send her every future manuscript I was to complete, into, as the contract specified, “eternity.” She would also represent any stage, film or television work that was to derive from the manuscripts of mine under her control, also into “eternity.” There was much other self-serving language, all of it to the benefit of the agent.

I think she did not understand that I was hiring her, rather than the other way around.

So, I wrote back to her, with a version of her contract that I had run through the Word “Track Changes” editing program. My edits released me from all the requirements the agent had put into her contract, except for the one that pertained to her representation to publishers of the one title I had sent to her. “After all,” I wrote, “we haven’t worked together, and I will want to see how you do with this first project.” I also added the proviso that if, after two years of her representation, she had not placed the book, I could opt to re-open the conversation about our contractual relationship, with the idea of possibly changing it.

I sent my edited version of the contract to her with a kindly letter. For some reason, I never heard from her again. Perhaps she thought me naïve.

The second gauntlet is filled with the major publishing companies. One of them, Ballantine Books, had published My Father In the Night in a trade paperback edition. When I attempted to interest them in my next book, I found that the editor who had accepted My Father In the Night had left publishing altogether. The new Ballantine editor had no idea who I was and, after an initial exchange of letters, brought an end to the conversation.

During the next twenty years, I wrote seven books of fiction, and could summon no interest in them from any agent or publishing company.

In the meantime, the internet was born and flourished. Along with it came the flurry of software programs that put the means of production for books into the hands of the authors. It took just a few years, but that did happen. It is a revolution. It also happened that, if as an author you pursued this path and you had sales, you would receive a significantly larger royalty payment per copy than you ever would have received under the previous regime of agents and corporatized publishers. Also, the entire panoply of book distribution opportunities remained as much in play for individual authors as it was for books published in the old-fashioned way.

You also, by the way, have much more control over your relationships with movie people, Netflix, Amazon Prime, et. al., since there need be no agent intervening in the conversation.

Sensing a breakthrough, I started publishing my own work about seven years ago. I had written almost all those books during the previous twenty years. The manuscripts had resided in desk drawers, cardboard boxes, and on computer hard drives. I resuscitated them all, had them professionally edited, designed, and produced, sold in print and ebook forms, and professionally reviewed (I must say, rather favorably in all cases.)

Thus, suddenly, I was “prolific.”

Contemplating that breakthrough, I had had conversations with many writers and publishing people about this whole notion of doing it all myself. An editor whom I had hired to edit two of those seven books, who remains to this day beyond famous for his work as an editor and as a publisher, told me, “Being published by Houghton Mifflin these days, Terry, is like being able to say that you were on the roster of the 1947 New York Yankees.” An equally well-known New York literary agent who is a close friend of mine told me a few years ago, “The great literature of the twenty-first century, Terry, will have been self-published.”

So there you have it…one brief history of a prolific writer.

Terence Clarke’s new novel, The Moment Before, will be published on September 1, 2021. It is the third of a trilogy. The others are titled My Father In The Night and When Clara Was Twelve. Those two are available everywhere, in print and ebook versions, as will be The Moment Before.

www.terenceclarke.org #fiction #writing #editing #publishing

These people are in charge of the San Francisco schools?

January 29, 2020

Regarding a recent seriously foolish move on the part of the San Francisco School Board, to change the names of several of the city’s schools, please see this article from yesterday’s The Guardian. If the people after whom these schools are named are to be criticized, use the moment as a teaching vehicle to enhance current students’ understanding of history. George Washington? Abraham Lincoln? Dianne Feinstein? Yes, none of these was (or is) a politically correct purist, and we can talk about that. But erase them from public notice, as the school board suggests?

I suggest sending the school board back to school.

Have them read the more than 16,000 books that have been written about Abraham Lincoln and the no doubt like number of books written about George Washington. And then, have them take a look at Dianne Feinsteins’s admirable handling of the murder of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone in 1978, whom she succeeded as mayor, and her ongoing laudable career as a solid liberal leader in the U.S. Senate. Thus taught about these figures in the much broader way that apparently was not provided by their education, perhaps the school board (about whom little has been written) will better understand the nuttiness of what they are proposing.

The End of San Francisco?

January 21, 2021

The famous Diego Rivera mural, The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City (1931), at the San Francisco Art Institute, is in mortal danger.

The Art Institute’s financial difficulties are well known in San Francisco, and the reasons for them are justly decried. The transformation of one of the warehouse buildings on the docks below Fort Mason into a second facility a few years ago was a mistake, both financially and aesthetically. It is an artistically pointless boondoggle that cost millions, and therefore a prime source of the Art Institute’s current troubles.

To alleviate the debt, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors has proposed selling the mural, assessed at a value of fifty millions dollars, to George Lucas, to be placed eventually in his Los Angeles museum. (For the details of the situation, click here.) Were that to happen, what is perhaps the most important single piece of art in San Francisco would leave the city. San Francisco and those here who place deep importance on the emotional and intellectual worth of fine art would be deprived forever. Mind you, I’m not speaking just of the well-fixed who sit on boards and contribute large sums to maintain San Francisco’s place as an art center. I am speaking of the many viewers one always sees looking at the mural (during non-Covid times, of course.) This includes the enormous Latinx community that lives in the city, and those other communities of color and ethnicity who find in the mural a staunch reminder of why it has such importance in the city’s remarkable racial history, good and bad.

Little can diminish the importance of the Art Institute to San Francisco, and to the city’s future. The Rivera mural itself symbolizes that importance. But also, a brief look at who studied or taught here establishes it as a major font of important American art. A few of those? Annie Leibovitz, Imogen Cunningham, Joan Brown, Richard Diebenkorn, Ansel Adams, Linda Connor, Manuel Neri, and David Park, among many, many others.

Without the Art Institute, San Francisco would take a major step backward. San Francisco State University, from which I received a master’s degree in English Literature, remains an important center for the visual, musical, and literary arts. But the Art Institute is its own deeply important entity and deserves the opportunity to save itself and to be reborn as the major arts institution it has so prominently been.

Here is a modest proposal…. The University of California recently bought the Institute’s debt. That purchase includes the ownership of the Institute’s building. The Institute itself now has a six-year lease on the building, which gives it a window to raise the funds to save itself without selling the mural. But, if that is unsuccessful, the property will become a permanent possession of the University of California.

And that would include the Rivera mural.

My proposal is that the University actively step in now and make the Art Institute of San Francisco a separate campus in the University of California system. Of course, it would be a place devoted to the visual arts, but I would also make it a principal home for dramatic writing as well as creative writing in general, film, video, acting, media arts, recorded music, performance studies, and other essential arts.

Something like the Tisch School of The Arts in Manhattan, part of New York University.

The current leadership of the Art Institute must also be relieved of their duties…immediately. For the last twenty years, the Institute has been diminished by poor decision-making and bad management. When the University of California takes over, this is the first change that must take place.

All this is pie in the sky, perhaps. But I don’t think so. The Institute can be remade into a vital center for the creative arts, as is Tisch, and a major source of those arts into the future. It needs fine, insightful management with a true business sense and the kind of major emotional commitment to the arts that, if the Art Institute disappears, will sink into real decline in this city.

The Institute and Diego Rivera’s remarkable mural are too important to San Francisco for that to happen.

Terence Clarke lives on Russian Hill, two blocks from the San Francisco Art Institute. The Rivera mural was a principal inspiration for his novel The Notorious Dream of Jesús Lázaro.

On Writing: Art That Isn’t There

January 5, 2021

Compared to the artists, critics remain in the back seat. Yet a very few have written marvelously about the graphic arts. When I first read E. H. Gombrich’s The Story of Art, I thought that being an art historian would be something to which I could aspire. The book is still a must for anyone who knows little about the history of Western art and wants to know a lot more. At the time, I knew almost nothing about that history, having survived university without ever taking the time to go to the school’s art museum. (That would be U.C. Berkeley.)

The trouble was that, by the time I did read Gombrich, I was in my mid-20s and married to an artist who had insisted that I read his book, maybe to make myself less embarrassing at art openings. I had also written a couple of unpublished novels. Those agonizingly arrived-at works nonetheless had convinced me that, really, I would be happier making my own art. The only disappointment was that my art would be made of the ever un-beautiful, gracelessly utilitarian words with which novelists have to work.

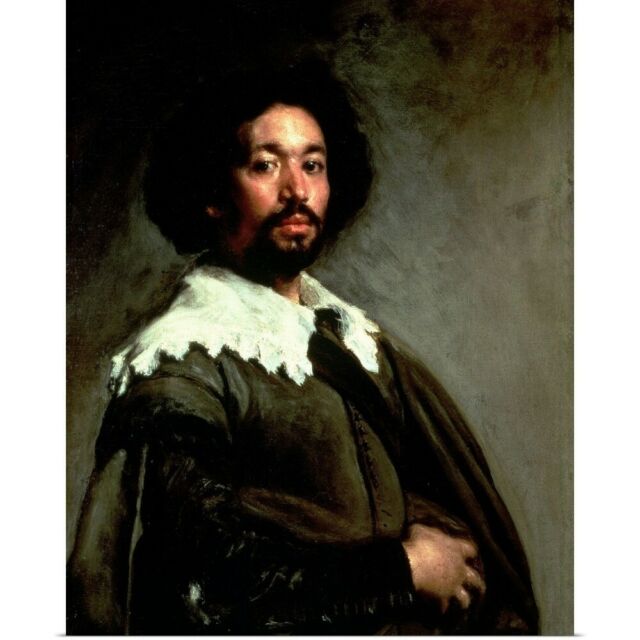

The tools—and the talent—that resulted in Velásquez’s portrait of Juan de Pareja were not to be mine.

I was able eventually to read sufficient criticism and history—John Ruskin, Robert Hughes, Kenneth Clark and others—to have serviceable enough knowledge to write about art. But it required my own imaginative powers to express how I truly felt about what I was viewing. I simply did not have the technical chops to explain how a painting works, either in terms of its shapes or the materials and tools used to make it. In the time-honored phrase, I knew what I liked.

The Mexicans interested me tremendously. For one, they weren’t Europeans, a single fact that goes a long way to explaining why they are so special. The unique mixture in Mexico of the vernal, myth-fueled sensitivities of the indigenous peoples and the crazy otherworldly enthusiasms of the Spanish conquistador artists made for something entirely unique. When I saw the great Rivera murals in the National Palace in Mexico City and the heart-chilling Orozco depictions of The Conquest at the then-orphanage in Guadalajara, I realized a more earth-bound pagan-animist consciousness than what I had read about in so much of western European, heaven-touring art.

Diego Rivera’s earth-mothers and and Jose Clemente Orozco’s flame-wrapped, man-angel swirling into the Guadalajara universe struck my heart.

I wrote a novel in which I created a fictional Mexican artist whose work has the same combination of fruitful grit and celestial transformation of these and so many other Mexican artists. He comes to San Francisco, California and determines to paint murals across the entirety of the outside of the Cathedral of Saint Mary in that city (which actually exists, at the corner of Gough and Geary Streets). The local archbishop thinks the artist and his ideas crackpot, and therein lies the tale. Jesús Lázaro is the artist, and The Notorious Dream of Jesús Lázaro is the book I wrote about him.

When I started it, I knew that I would have to describe Jesús’s fictional art. What I had always thought necessary in writing about actual art became, precisely, the task at hand. But while the Mona Lisa has qualities that are abundantly evident, in my case the paintings I describe do not exist at all. So, my writing took on all the responsibility of providing for the reader’s emotional response. The reader of my book can only imagine the painting, and I have to give him/her the words that bring that imagining to flower.

That’s difficult enough when you’re presenting some sort of social scene, which is the basic stuff of almost all fiction. But describing an entire individual piece of art that is so ephemeral as to not be there at all is a different task. Luckily for me, it was a lot of fun, which lightened the burden considerably. But nonetheless, I would love to view Jesús Lázaro’s paintings, wherever they may be, to see if I got them right.

AND… I’m at it again! I’m in the middle of writing a novel titled The Moment Before. The main character, Yvette Roman, is a renowned Parisian artist who suffers from a rare form of severe epilepsy. In the moments before a seizure, she encounters exotic visions so important to her heart that she feels she must paint them. One day, though, a masterful forgery of her work shows up at her New York gallery. She has no memory of having painted it. So it must be a forgery, mustn’t it? But could a forgery actually be the best piece she has ever done?

Yvette’s affliction itself is based on the fact that my father was, and my son is, epileptic. I am not, so that here too I have to imagine what Yvette is going through. If you would like to know about the importance of this in my own life and work, you can read my essay titled “Fathers, Sons, and Seizures.”

The novel will come out in 2022.

#fiction #fictionwriting

(The Notorious Dream of Jesús Lázaro was published in 2015. It is available in bookstores everywhere and at all the usual online sites.

“Tinta Roja”…Depending on the singer, it can break your heart.

“Tinta roja” is a much-loved tango that was written in 1941 by Sebastián Piana and Cátulo Castillo. It has been recorded by most of the important tango orchestras with singers of equal distinction. Here are three versions of it, by three different singers, in three very different styles.

The first, by the orchestra of Anibal Troilo with the voice of Francisco Fiorentino, has an old-fashioned sweetness that, although beautiful, does not for my money represent the disaster that is told by the lyrics. I think Troilo was trying for the kind of heartfelt nostalgia for a lost youth that is featured by so many tangos. But it doesn’t work for me here because, in the second half lyrics of the song, the feelings express such barren loss. Here it is.

The second version is sung by Roberto Goyeneche, the famous “Polaco.” A man of the streets (before he was discovered, he was a Buenos Aires municipal bus driver who would sing tangos without accompaniment while driving. That’s how a record producer found him.) Goyeneche’s version of “Tinta roja” has a harder heart. His sadness in this version is much more authentic than that presented by Fiorentino. The orchestra behind him (also that of Anibal Troilo) surges through the song with almost Hollywood-style over-arrangement. But for me, Goyeneche’s voice saves the day. This man ‘s anger is lined with sadness.

The third version is a very contemporary one, sung live by Ruben Juarez, who accompanies himself on bandoneon. I believe Juarez, in both his playing and singing, catches the despair and fury of “Tinta roja’s” lyrics. The man walking about in the dark alleyway of this tango is coming apart. He suffers quietly sometimes, angrily at other moments, enraged finally. For me it is the most authentic version of this tango I’ve ever heard. See if you agree.

Here are the lyrics to “Tinta roja,” first in Spanish, followed by my translation to English:

Tinta Roja

Paredón,

tinta roja en el gris

del ayer…

Tu emoción

de ladrillo feliz

sobre mi callejón

con un borrón

pintó la esquina…

Y al botón

que en el ancho de la noche

puso el filo de la ronda

como un broche…

Y aquel buzón carmín,

y aquel fondín

donde lloraba el tano

su rubio amor lejano

que mojaba con bon vin.

¿Dónde estará mi arrabal?

¿Quién se robó mi niñez?

¿En qué rincón, luna mía,

volcás como entonces

tu clara alegría?

Veredas que yo pisé,

malevos que ya no son,

bajo tu cielo de raso

trasnocha un pedazo

de mi corazón.

Paredón

tinta roja en el gris

del ayer…

Borbotón

de mi sangre infeliz

que vertí en el malvón

de aquel balcón

que la escondía…

Yo no sé

si fue negro de mis penas

o fue rojo de tus venas

mi sangría…

Por qué llegó y se fue

tras del carmín

y el gris,

fondín lejano

donde lloraba un tano

sus nostalgias de bon vin.

Translation:

Red Ink

Thick wall,

Colored red in the grey

Of yesterday…

The feelings

Of the happy brick

In my alleyway,

With a smudge

Coloring the corner…

And to the cop’s badge

That in the thickness of night

Celebrates the end of its beat

Like a simple brooch…

And that carmine-colored mailbox,

And that little tavern

Where the Italian guy weeps

For his faraway blonde amor,

Washing it down with a glass of good wine.

Where will my neighborhood be?

Who took my youth away?

In which corner, my moon,

Were you emptied, as you were,

Of your clear happiness?

On the sidewalks that I walked,

The bad guys now no longer there,

Beneath your flattened sky,

There walks in the night

A piece of my heart.

Thick wall,

Colored red in the grey

Of yesterday…

The boiling over

Of my sad blood,

Shed on the little geranium

On that balcony

That hid her…

I don’t know…

Was it the blackness of my pain

Or the red of your veins,

Blood of mine?…

Why did she come and then go,

Passing the carmine

And the grey,

And the faraway tavern

Where the Italian wept away

His wishful longings with a glass of good wine?

The translation to Spanish of Terence Clarke’s novel, The Splendid City, with Pablo Neruda as the central character, was published on December 1. Titled La espléndida ciudad, is available in bookstores worldwide and at all the usual online sites.

“Thank you, but No.”

December 1, 2020

I’ve always had faith that I could write, which I began doing seriously when I was in my early twenties. A couple of my books were published in the late 1980s and early 90s. But after that, I couldn’t get anyone interested. This was pre- or early-internet time, and we had not yet seen the founding or early struggles of a couple of important businesses: Amazon particularly, Facebook, Twitter, et.al. In those times, the road to publication lay through a series of bottlenecks that made publication very difficult indeed. Those would be the community of literary agents and then the publishers themselves. Both these groups had a kind of monopoly on who would get published and who wouldn’t.

For the majority of fiction writers in the United States, if not all writers, the bottlenecks became the bloodied fields of failure. There are thousands and thousands of writers with completed manuscripts, and a few hundred who get published every year. Those few are the ones selected by literary agents (most of whom are in New York City) for representation. Established publishers will not look at any projects that are not represented by an agent. So, if you write and wish to be published in that system, your chances of success are slim to none. (I read a statistic once that, on any given day, there are 120,000 manuscripts in the U.S. postal system, making their ways from the authors to some publishing person or another. Of those, few will indeed be published. The rest lose.)

It has been this way for many, many years.

For the first few years of my writing with serious intent, I put myself firmly in the middle of it all by following the rules. I wrote earnestly and often to agents. I followed their stringent rules to the letter, for submission to their agencies. I waited the de rigueur two to six months for a response, which was almost always “Thank you, but we find your fine work not quite right for us,” or some such. Those responses, of which there were hundreds…many hundreds…put me completely out of the running for establishment publishers, for years.

In the past twenty years or so, however, we’ve seen the advent and growth of viable publishing possibilities that circumvent this self-important and ruinous system. The possibilities came about with the advent of the internet and those companies I mentioned above, with some others. Prior to those events, if you were an author and self-published your books, you would be committing professional suicide, even if your books had real value. Agents and publishers, once they learned that you had self-published, would not look at your work at all, since self-publishing was viewed as an instance of authors accepting their own failure. Also, as a side-issue, the companies that did do self-publishing expected the author to carry the entire burden of producing and distributing the books. They charged the author handsomely for both those services. The reading public for such books was made up of the author’s family and a few friends. Otherwise the author was sunk.

But now, all this has changed. Books can be tastefully designed, produced, and sold using all the tools of online marketing that we now know so well. Also, because of Amazon (and Apple Books, BN.com, and other companies) the author has an open door to the world book-reading market, in printed and digital products. Also, the author will usually make a per-copy royalty that is twice or three times the amount he/she would receive from the established publishers. So, if you get $1.50 per copy sold as a royalty from Houghton Mifflin, you’ll receive a royalty of three or four dollars for each copy produced and sold outside the established publishing system. The established publishers used to carefully edit, market, and publicize their products. Budgets for those things have been uniformly slashed by all the established publishers, especially since most of them have been taken over by corporate conglomerates.

So…there is that expense that the author must shoulder himself/herself. The good news is that the author gets to control what’s happening there, in ways not even imagined just a few years ago.

With all this, the influence of the long-established publishing community, which is still gigantic and worldwide, has lessened. But the fact is that now, for the first time in publishing history, the means of production are in the hands of the author. One noted literary agent of my acquaintance said this to me two years ago: ”Terry, the great literature of the 21st century will have been self-published. Don’t even consider wasting your time with the New York crowd.” A very noted editor with years of experience in the New York trade, who worked with me on two of my novels, said this to me: “Having your book come out these days from a huge publishing house is like having played on the 1947 New York Yankees team. Who cares?”

Of course, Amazon is not perfect, as we all know. But that is another story.

(Terence Clarke’s new novel, The Moment Before, will come out in 2021. The translation to Spanish of his novel about perilous events in the life of Pablo Neruda, The Splendid City, is being published today, December 1, and is available everywhere worldwide. The title? La espléndida ciudad.)

The Splendid City (North) vs. La Espléndida Ciudad (South)

October 6, 2020

I speak Spanish, which I learned as an adult, and I write in English. But to write a full novel in English about one of the principal Spanish-speakers and writers of the last hundred years does present a challenge. This despite my having translated three of that author’s books to English.

I had read about the very dangerous passage that Chilean poet Pablo Neruda made in 1949, escaping from Chile to Argentina on horseback through the Andes Mountains. He had been barred from his senator’s seat in the Chilean Congress, and there was a warrant out for his arrest…all due to grave political disagreements with then-president Gabriel González Videla. It was decided by the Communist Party in Chile, of which Neruda was a member, that the only way to get him out of the country safely was on horseback through the Andes. It was a very dangerous undertaking in which Neruda was led through the cordillera by trackers familiar with the territory. Despite very rough conditions and a couple of close brushes with death, they completed the trek, and Neruda was able to move on to Paris, where his wife Delia del Carrill was awaiting him. He went on to even greater international fame and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1973.

I succeeded in finishing the novel, which has the title The Splendid City, and it was published in 2019. I’ve always thought that there would have to be a Spanish-language translation of the book, Neruda’s fame and readership in Spanish-speaking countries being of legendary proportions. Through a friend of mine, a prominent Chilean novelist living in the United States, I made the acquaintance of Jaime Collyer, who is himself a noted novelist and short story writer, and a prominent figure in contemporary Chilean writing. We talked. Jaime read my novel (he is remarkably fluent in the English language) and liked it. We decided to work together.

So…La espléndida ciudad will come out in its Spanish-language edition on December 1, 2020 in the translation by Jaime Collyer. It will be available in bookstores everywhere (especially, of course, in Central and South America) and online at the usual sites.

Despite all this, which was pretty fast-moving for me and exciting, I worried that because the original is in English, a Spanish-language translation wouldn’t have the kind of authenticity that such a book would have, had its author been hispanic. English has such a northern European twist to it (a combination of Celtic, Britannic, Germanic, Danish and who knows how many other frozen-tundra linguistic elements) that a rendering of it into Spanish may not have the sunny, warm-breezes, wine-induced, olive-oil Mediterranean flow that such a story deserves.

You realize that this is a real possibility once you’ve studied the two languages and understand the difference in feel, one from the other. For me, a romantic tale is not the same in English as it is in Spanish. (I’m talking about the languages here and the cultures they represent. To talk about the more carnal differences between the two peoples is another matter altogether.)

Luckily, I have read many, many Neruda poems in Spanish as well as his very entertaining memoir, Confieso que he vivido (I Confess That I Have Lived). So, I have a ready sense of his often breezy and very adventuresome writing style. Neruda is a poet who goes out on a limb almost constantly. You have to pay attention to what he’s doing, while at the same time relaxing and flowing with it. That attention is often super-rewarding, although not always. (To punish yourself a little, read Neruda’s political poetry, most especially his odious “Oda a Stalin.”)

I decided to go out on a limb myself. Neruda describes his escape in Confieso que he vivido, but in just thirteen pages. It’s cursory and quick, hardly satisfying if the reader wants to know everything about this extraordinarily dangerous trek. In his account and those of his biographers, there are place names or hints about the weather, the mountains, and occasional dramatic moments. But not enough to give us the real story in detail.

Realizing that Neruda is himself a fantasist in so much of his work, I decided to be one in my novel. I put him and the others in the situations that he describes; but then I made up what happens in those situations mostly out of whole cloth. For example, the trackers lead Neruda into a lava tunnel (a common result of volcanic activity when hot lava makes a stream for itself through the volcano’s rocky structure.) Neruda and his helpmates did indeed encounter such a tunnel (by now millions of years old and, thankfully, free of the searing lava flow) and passed up it. But what they see in that tunnel, as described by me, is complete fantasy. No such visions have ever been found in South American caves as far as I know. There are several other very unlikely events in the novel, including conversations with long-dead gauchos condemned to wander through these terrifying mountains forever.

To my great pleasure, Jaime understood what I was trying to do in those sequences, and his translation honors the adventure that is presented in them…adventure both historically accurate and thoroughly made up, fantasms and all, by the author.

My hope is that I’ve written a South American-Mediterranean novel, despite my own rainy, teeth-rattling, Irish-English, cold weather antecedents.

Terence Clarke’s most recent novel, When Clara Was Twelve , is available in bookstores everywhere and online.

Writing Begins in Borneo?

Fiction doesn’t come from nowhere. Every piece of fiction finds its beginning in the author’s direct personal experience, humble as it may be. The fiction that results is seldom just a fact-by-fact narration of the experience, although the experience does provide the basic starting point. It’s the storyteller’s verve that brings the final fiction to full flower. Dickens, Cervantes, Austen, Morrison…the works of all of them have such simple roots. Yours can come from a whiff of a rose’s petal or a dream vision of the beginning of the universe…and everything in between. But it has to start somewhere in your day-to-day.

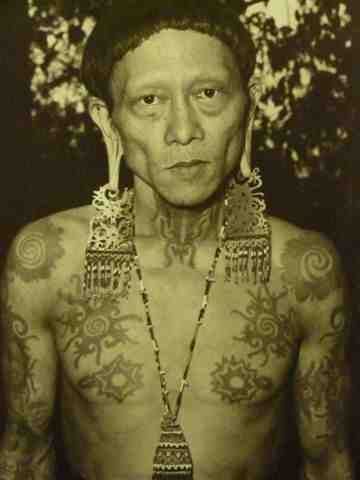

I served in the Peace Corps in Sarawak, Malaysia, on the island of Borneo, from 1965 through 1967. I was twenty-two when I arrived. I had seldom set foot outside of Oakland, California (well, I did go to Berkeley for five years, a distant few miles from Oakland) and I left the United States with my father’s words ringing in my ears. “Terry, why are you doing this?” I was originally supposed to go to Côte d’Ivoire, mainly because I had studied French in university. But the Peace Corps notified me that they had enough volunteers in that nation for the moment, and would I consider Malaysia? I did not know where Malaysia was. I didn’t look it up. I simply said yes, and some months later I arrived in Kuching, Sarawak, a city on the island of Borneo.

Malaysia is in Southeast Asia, to the south of Vietnam. (I did know where Vietnam was, of course. What American didn’t, in those times?) Malaysia was a new nation, an agglomeration (at least for the while) of the Malay peninsula south of Thailand, the island city of Singapore at the tip of Malaya, and the territories of Sarawak and Sabah, which together take up about a quarter of the island of Borneo, three hundred miles to the east across the South China Sea. All former British colonies, they had recently been abandoned by their Limey overseers, cobbled together as a nation, and sent off on their own.

My job was to help set up an English-language primary school system in the upriver regions where Iban tribesmen lived. (The English-language use was the Malaysian government’s idea, and I’d be glad to tell you about it some other time.) A war was going on at the moment between Malaysia and Indonesia, along the north-to-south border that separates the two nations in Borneo. The Ibans were much affected by all this and had abandoned many of their jungle longhouse villages because of that war. The new Malaysian government had set up downriver refugee camps for these Ibans, and I lived in one for the year and a half that I was going up and down the Skrang River setting up schools.

Many of these camps were being run by British officials, leftovers from the recently abandoned colonies. I met one, a man named Craft, who was in charge of a government rubber plantation near the refugee camp in which I was stationed. We had met because a Scotsman who had been in Sarawak since the Second World War and was married to an Iban primary school teacher introduced us.

Craft, the Englishman, was a singularly offensive man who embodied all the clichés that we’ve seen in British movies that feature self-congratulatory Brits lording it over the natives. He wore the de rigueur tan British walking shorts, white shirt, tan long socks, and brown leather shoes. He spoke some brand of the King’s English that would fool you with its elegance, even as the ideas being expressed were self-important, silly, and frequently violent. Craft’s white skin was actually red, rather like a new brick, I thought. The cause was a combination of the years of strong sunlight in which he had worked and the strong whiskey that he seemed to imbibe all day long. You consulted with Craft, if you had to at all, before noon on a given day. After that hour, you could expect whining, racist complaint for the rest of the day, fueled by the alcohol.

McGregor, the Scot, was well known in Sarawak for his complete understanding of the Iban language and its culture as well as being a fine rubber man who knew his trade. He always had the respect of the Ibans whom he trained and who worked for him. He also had a very thick Edinburgh accent that made conversation between him and me almost always comic. We made fun of each other’s strange manner of talk. My Californianisms often brought him to glee. “How is it, laddie,” he once asked me, “that anything gets done in that bloody place when you talk so strange?” We occasionally had to give one another vocabulary lessons.

One Saturday, while I was visiting with Craft and his wife, who was also British and red-skinned and, I had learned, could not bear her husband, an Iban came to their house in a panic. One of the Iban workmen had slashed his right leg with a machete and was bleeding badly. Swearing, Craft went into the house to get the keys to his Land Rover. I knew that he spoke no Iban, which I did, and I asked if I could come along to help. I had invaded Craft’s territory, I guess. He told me drunkenly to mind my own fucking business, Yank, and then held up a moment, to tell me that all my innocence and sobriety was just a ruse out here in this goddamned swamp where you couldn’t trust a bloody Iban to even know how to swing a goddamned machete. “So what help could a fool American be?”. He climbed into his Land Rover and was gone.

So was I. That was the last conversation I ever had with Craft.

Many years later, when I was finally writing stories based on what I’d seen in Sarawak, I remembered him and a scene I had witnessed in his office between Craft and McGregor’s then seven-year-old son. The boy spoke an amalgam of Scots English and Iban, a lingo that I and McGregor enjoyed quite a bit, but that was insulting to Craft. He had once said to me in private that English was bloody English, and that Iban was gargle, and “that boy can’t seem to negotiate either one.”.

I wrote a story titled “The Wee Manok,” in which all these characters appear in fictional form. It is one of several in the first book of mine ever published, titled The Day Nothing Happened. It came out from Mercury House in San Francisco (sadly now defunct) in 1988, and was edited by the wonderful Alev Lytle Croutier, with whom I am still close friends.

The Day Nothing Happened will be published in a new edition next year.

“The Wee Manok” ends rather differently from how I just described my experience with Craft himself. That’s okay with me, though, since his form of self-serving cruelty is of little interest and would make for bad fiction. He’s far more interesting to me in the way that I re-invented him for “The Wee Manok”, because I gave him a conscience. That ability to change one set of expectations (i.e the basic facts) into quite another (i.e. the final written story) is one of the great pleasures of doing fiction.

“The Wee Manok “ is available in digital form on Amazon. (Note: you’ll need the Kindle app, which is available at no cost for all devices.)

#fiction

#fictionwriting

Gosh, it’s cold out there!

August 11, 2020

No one wishes to be frivolous about the current pandemic. It’s real and should be respected. Wear the mask. Don’t stand close. Pay attention to who is around you. Etc.

There is an aspect of the virus, though, that for me is no problem at all. I spent many years in corporate business, an endeavor that I did not much enjoy and am glad to have left, a departure that took place about fifteen years ago. Business did allow me to make some money, which very much helped in raising a family. It also enabled me to hone my skills as a conversationalist, skills that were always with me anyway, even without business. (Although, these days, business is so often done with computer engineers, with whom it is almost impossible to carry on a conversation. They know so little—I mean, what can you say with just a zero and a one?—and have few tools to clearly express that vacancy. But that’s another subject, for another day.)

I’ve been pursuing a different profession since I left business, which is to write fiction. One can argue that that’s hardly a profession, since it is close to impossible to make enough money to support yourself and a family on creative-writing-wages. But the one thing you must have to make that pursuit fruitful is time alone. I suspect no one has ever completed a novel while working in one of those workplace offices that have been the rage for the last few decades. Everybody in one room, long tables, workstations everywhere, noise and blather everywhere, and no privacy.

For the writer, solitude is the requirement for doing fiction. You are always alone and, if you have talent, are always involved in a complicated conversation with yourself. This sort of thing can often be difficult, which I think explains the bad fiction being written today, which, as far as I can see, is most of it. In a turmoil-ridden, dark world, many fiction writers fall into the trap of being driven into that darkness. So, these days we have buckets of novels written about how featureless life is. They are often slim volumes about small lives, in the manner of, say, Camus’s The Stranger, as in this, written by Camus himself: “She wanted to know if I loved her. I answered the same way I had the last time, that it didn’t mean anything but that I probably didn’t.” It may be that Camus was a good writer…maybe. At least he’s interesting in his character Meursault’s emotional dismissal of himself and everyone around him. But most of the contemporary novels that I’ve attempted reading that try to explain the current emotionally plain, viewless atmosphere are themselves viewless. Plain, as well. Yes, they give you an idea of what it is to live in these times of Corona virus shutdown and braggart presidential cluelessness. But, to get that, all you need do is look around. To write well about it is another matter. Simply spelling out the emotional failure that is the main subject of contemporary fiction —- one novel after another —- isn’t enough.

But, of course, the fine novel, rare as it is, is out there. You must keep looking. At least for now, García Márquez will have to do. His work still has it in spades, although his time has passed. Edith Wharton too, although even she would have trouble these days, since so much of her work depended on fascinating conversation between compelling women. Wharton’s characters were unhappy, but very much more than just unhappy.

It’s out there, that novel. It’s being written now…somewhere. We mustn’t give up. We’ll find it.

Terence Clarke’s novel The Splendid City, with Pablo Neruda as the central character, has been translated to Spanish by Chilean novelist Jaime Collyer. It will be published as La espléndida ciudad later this year.

#fiction #writingfiction #literaturaenespañol