Home » Writing (Page 2)

Category Archives: Writing

OMG!@e-speak

In the history of literature, the genre of the letter has been a very important element. Epistolary exchange has shed light on the lives of most of the important artists and historical figures — and some less important figures that happened to have written well — in the history of the world.

This light has revealed profound emotional difficulty and expressions of love… savored love, questioned love and destroyed love. Letters often exposed the high comedy of family disputes. The horrors of war were made memorable in letters from the front, while the onerous effects of preposterous government or church intrusion on the sensuous spirit were brought into the open. The letter, as a form, shed clear light on just about everything.

Now we have email. When I first encountered this phenomenon several years ago, I was heartened. With the birth of the telephone and, much later, the television, good personal writing had abruptly disappeared. It was easier to pick up the phone and call. It was more fulfilling to watch a game show than to write to your lover. So, most people gave up writing letters, and an entire literary genre almost ceased to exist.

Email held out the possibility for a resurgence of the letter-form through use of the Internet. Perhaps now people would write to one another again, a consummation devoutly to be wished. The letter is so important to the history of human affairs that its disappearance was like the withering away of a human organ, one that spirits the blood and makes it flow. Email would restore that organ, I hoped.

It has become apparent, though, that email has not risen to the challenge.

Letters hold together. Emails often have nothing to grab on to. Letters call for contemplation and soulful enjoyment. Emails call for very little. Letters contain cries for understanding, personal descriptions of terrible events or recoveries of soul. Emails tap-tap-tap across a depthless surface, asking only that they not be ignored, which they so often are. Letters contain a beginning, a middle and an end. Emails are dull wisps of nothing, written in as few characters as possible. It is this kind of artless dodging of anything important that is the norm in email and in its little brother, texting. And texting’s little brother, the tweet, is now the perfect email.

So my wish for the return of real writing has not been fulfilled. This is due to something I had not foreseen at all, which is that although the usual emailer may want exchange of some kind (perhaps a revised bill of lading, a recipe for goulash or Miley Cyrus’s URL), an email generally is not exchange. It almost never cares for good writing. The email is a depthless, short, ungrammatical demand. There are slightly meaningful emails, to be sure, like those that talk about one’s cat or how to screw in a light bulb. But even emails like these are random momentary conversations that go nowhere, or at least not far.

And now, horror of horrors, we have the Twitter novel, which somehow I feel is not destined — at least yet — to deny Dickens and all those others their insurmountable place in the pantheon. But it might. We will have seen the end of human transcendence on this planet when a chapter like number 42 in Moby Dick, on the whiteness of the whale, which is surely one of the most lyric and strange pieces of writing in the English language, is replaced by a chapter of 140 characters that have little to do with each other, as is the case with most tweets.

So, for the vast majority of this new language I propose the term “@e-speak.” The word could be an adjective, a kind of descriptive term that refers simply to the nature of the email/tweet itself. For example, you read a short little tweet, of a few impenetrable words and signs, with no capital letters and no punctuation, something about nothing written in illiterate language. It rattles with @e-speak inconsequence. That’s an adjective.

My use of the term would also make it into a noun. @e-speak is the language that, in another context, would be called gibberish. OMG!

Terence Clarke’s New York story “Everyone in L.A.” is available at Amazon.com. Visit him on Twitter…

How’s That Novel of Yours Doing?

The wish for fame, so illusory a thing, can kill you. Or at least, it can kill your novel.

The wish for fame, so illusory a thing, can kill you. Or at least, it can kill your novel.

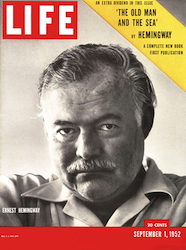

In an essay in The Spectator in 1711, Sir Richard Steele wrote that it is “the worst way in the world to Fame, to be too anxious about it.” For almost all of us who took up writing in order to be like Ernest Hemingway, this is good advice. The Hemingway goal hasn’t worked in my case or, I suspect, in that of most others who have had so markedly specific an intention. Perhaps all others. This is so because such a goal has nothing to do with writing well. It has an awful lot to do with churlish envy, as well as what we know about Hemingway, that he marketed himself almost from the beginning in order to get where he got.

Perhaps his remarkable fame derives from the great interest there has always been in his adventurous life. But I think his adventures had little to do with his ability to write well, as he so often did. In his writing, he sought to please his one greatest fan, which was himself, and for this steadfastness he deserves the congratulation he gets.

When I began writing seriously, I had the theory that writing fiction was a public, not a private, endeavor. Because it is so intense a form of communication, it seemed foolish to me to write without the idea of getting published. Publishing with an established firm, either major or minor, was then the only way of getting your work in front of a public. So, without publishing, there was no communication, and without a public, writing to me wasn’t worth doing.

But then, as now, there was a gauntlet that writers had to run, to get to the golden moment of publication by a major U.S. publisher. Like a great moat surrounding an obdurately faceless castle, the army of literary agents floats about, thick with weeds and goo. Any writer who has spent time in these waters has a library of favorite phrases that he or she has learned from agents. “Your work has significant integrity, but needs to be fleshed out a bit more.” “Though excellent, it’s just not right for us at this time.” “You’re clearly a writer with great promise, and we wish you the best in your search for representation elsewhere.” “Couldn’t possibly sell this in today’s difficult market.” And many more.

The single best one my work ever evoked came from an agent employed by a West Coast firm, both now very long gone. The entirety of his communication to me read, “Wooden, foolish, a little bit trite… But, thanks!”

Until the advent of self-publication on the internet, two-thirds of the manuscripts published in the United States in any given year by major companies were represented by literary agents, and to this day, when you look at the submissions guidelines for most major publishers, they say that they will not consider “unagented” work. So that seems pretty open and shut. If you want to publish with one of the Big Six, you need an agent. Thus you go swimming — because you must — in the moat, an experience that, if you do not have a ribald, very well oiled sense of confident humor, will drive you nuts.

Dealing with the major publishers themselves — should you survive the moat — is much easier because you have a goal, they are demonstrably interested and they know who you are. It’s just you and your editor, and you have a common wish.

There is a second problem with the Hemingway ideal, a problem spelled out succinctly by Richard Steele. If you write to be famous, the quality of your work will almost certainly be damaged by the anxiety with which you’re writing. You have the memory of all those great books, written by writers you admire tremendously, and there comes the time, often, when you worry that what you do will never come up to the level of what they did. You finish writing a paragraph or two, then you recall Joseph Conrad writing about something similar, or Joyce or Greene or Ellison or Dickens or Austen, Eliot, Nabakov, Baldwin, Faulkner… You stop writing. Or you continue on, the shades of all these others standing behind you, dark, celebrated, bookish shades brimming with talent, writers now long dead except for their great fame. You sense them watching what you’re doing.

It doesn’t work, and you won’t make it.

When I finally understood this and backed off, my writing improved and I started getting published. Right away. It was a simple, one-to-one relationship. Now I pay occasional attention to the idea of fame, when I’m reading about Lady Gaga or some such. But I never allow such a thing to affect what I’m doing. Fame is something others bestow upon you. Good writing is what you bestow upon yourself, your own most faithful, loving, and observant fan. If you don’t write for the emotional benefit of that reader, I believe your chances for fame will vanish.