Home » Posts tagged 'Irish Americans'

Tag Archives: Irish Americans

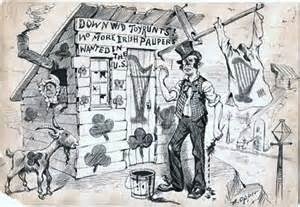

No Irish Need Apply

On a recent St. Patrick’s Day, a Latino friend whose family has lived in Arizona and California since before 1848, asked me “What immigration problem?” He leaned far over the cappuccino on the café table between us, shook his head slowly and then looked up at me once more, a smile on his face. “Are they talking about all these gringos that have been showing up around here?”

On a recent St. Patrick’s Day, a Latino friend whose family has lived in Arizona and California since before 1848, asked me “What immigration problem?” He leaned far over the cappuccino on the café table between us, shook his head slowly and then looked up at me once more, a smile on his face. “Are they talking about all these gringos that have been showing up around here?”

He refers to California — where we both live — and the Southwest as “Occupied Northern Mexico.”

Recently the nation has been in the throes of a debate about immigration. The immigrants being identified by the right wing of the Republican Party as threatening to the American consciousness and economy are mostly Central Americans, more specifically Mexicans. They are uneducated, we hear. They take jobs that should be reserved for American citizens. They don’t speak English. They got here illegally, and are coming in droves.

In their Pulitzer Prize-winning book Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, Edwin G. Burroughs and Mike Wallace write about the 1842 founding of a new political party in New York — called the American Republican Party — the main platform of which was anti-immigration:

What tied these disparate groups [merchants, professionals, editors and shopkeepers] together was a shared Protestant culture, a nostalgic belief that New York City had been a far better place just after the Revolution, and the conviction that the evils now afflicting it — rising rates of crime, pauperism and immorality — were foreign imports. The party wanted to extend the naturalization period to twenty-one years.

The particular group that offended the party then was the Catholic Irish. In the previous four years, about 60,000 of them had immigrated to the United States — almost all of them to New York City — to escape the economic and religious policies of the Protestant British government toward the Irish in their own, now long-occupied, country. The problem was far worsened by the Irish Potato Famine of following years, during which one-fourth of the population of Ireland left that country, most of them coming to the United States.

By the 1980s, the Irish in the United States had for the most part transformed themselves. In The Columbia Guide to Irish American History, Timothy J. Meagher writes, “The achievements of Irish Catholics now did not merely surpass Irish Protestants but carried Irish Catholics finally into the highest reaches of the American economic hierarchy … They appeared to have made it everywhere.”

The Irish, of course, are no angels. One need only read about the Civil War draft riots in New York City in 1863, during which Irish gangs took the opportunity to lynch many black people whose release from slavery, they felt, was the cause of the draft that was forcing their boys into the war. Also, a look at the history of the desegregation of public schools requires the telling of how Boston Roxbury Irish attacked yellow school buses taking black kids to white schools in 1974. There are many such stories.

Nonetheless, things had changed, and as it was with the Irish, the current hate-ridden xenophobia about illegal immigration will prove to be ill-advised.

Central American immigrants do not particularly want to leave their homeland. But as with the Irish, local economic conditions, issues of personal safety, and an atmosphere, in their countries, of government indifference to their plight, make travel to the United States a necessity. Surprisingly, the values that the Republicans say they espouse — the importance of family, daily prayer, a belief in hard work, insistent religious comportment — are indeed espoused by a great many Central Americans entering the United States. One would think that these are the kinds of people that the Republicans want.

But the Republican right wing’s flailing for power seems more a clear effort to bring about radical social re-engineering (getting rid of Planned Parenthood, for example, dismantling women’s rights, re-demonizing gay people, destroying what is a balanced –and popular– national health plan and imposing Christian sentiments on what is basically a pluralistic, democratically-elected, secular government), and less an embracing of democracy and its ideals. It voices its pious nostrums in order to wrest that power to its party’s agenda, while the Central American immigrants are here simply to practice their version of the American dream, which has always been the democratic ideal in this country.

Because of that, I believe, these new immigrants will formulate much of the history of this country in the 21st century, as the Irish Americans did in the 20th.

The stories in Terence Clarke’s collection Little Bridget and The Flames of Hell tell of the Irish in contemporary San Francisco.