There is a difference between education and training.

Education is an exploration of the soul—aided by deep study in the arts, creativity and the hard sciences—that opens the door to what it means to be human. It is the search for beauty and the understanding of it, or for the perfecting of newly artful inventions that deepen the possibilities for emotional depth and the advance of civilization.

Training is what you get when you want to perform a pedestrian task.

Peter Thiel has been very well trained. The co-founder—with Elon Musk and some others—of PayPal, and a member of the Facebook board, he was recently named by Donald Trump as a delegate to the upcoming Republican Party convention. According to Forbes magazine, Thiel is worth $2.7 billion, and in some circles he is world famous. He also feels that a university education is of little use in our times. He has been quoted as saying. “A diploma is a dunce hat in disguise.”

This despite the fact that his alma mater Stanford, along with several other institutions—Berkeley, University of Chicago, Harvard, Yale, NYU ad. infinitum.—continue fueling the enormous breakthroughs in the advance of the arts and sciences that have always been emblematic of the American university system. His attitude toward higher education is for me even ironic, given that, among his other degrees, he holds a bachelor’s from Stanford in philosophy.

A recent article by Tom Clynes in the New York Times tells of The Thiel Fellowship, founded in 2010, “which each year would offer 20 ‘uniquely talented’ teenagers $100,000 to forgo college and pursue ‘radical innovation that will benefit society.’ Today’s future Zuckerbergs shouldn’t be wasting time in lecture halls and football stadiums; they should be building businesses.”

The trouble with this is that it implies that the founding of businesses is some sort of end-all, and that, ipso facto, business is the reason for existence. But for that existence to be a successful one, the business endeavor needs to be accompanied by sophisticated and soulful—which is to say, actual—education, so that the businesses that are founded be relevant to the maintenance of civilizations and good for the business founder’s own soul…and those of his employees, of course. These Thiel fellowships throw the baby out with the bath water because of the totality of their rejection of actual education.

There are difficulties in the education system, to be sure. One reason for Thiel’s low opinion of the college degree may derive from the almost constant attacks on funding of public education by conservative and/or libertarian elements in state and federal governments. This too is an irony, given Thiel’s own libertarian leanings. He complains about what his cohorts cause. Also, it used to be that universities were centers for real learning, and therefore were devoted almost exclusively to studies of the liberal arts. Literature. Music. The graphic and plastic arts. Philosophy. History. But subjects that once trained people to perform tasks have now ascended to prime importance in most universities. So…engineering, business, technology.

Influenced by this change, the purpose of actual education is being degraded to some degree by the current rush among universities to improve the bottom-line. But real education has never been a slave to profit and loss. Rather it lives in the soul, where such notions as creativity and emotional intelligence reign. Experiment. Discovery. Understanding.

It is true that, in the arts, a certain dimming of the intellect is taking place in some institutions. In my own field, the study of literature has been badly eroded by the theories of deconstruction posited by people like Jacques Derrida and Paul De Man. It’s impossible to say whether these theories have any value, because the language with which they are explained is so filled with academic jargon, tortured syntax and gibberish thinking. Luckily, we always will have William Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, Octavio Paz, Gabriel García Márquez and the countless others, who keep the ship so admirably afloat and, with their excellence, simply thumb their noses at the deconstructivist nonsense.

Thiel has been quoted as saying that “the core problem in our society is political correctness.” This is very far from so. Other problems are much more important. The almost universal political silence about the need for world-wide availability of—and training in—birth control procedures, which would alleviate, if not solve, the problems of over-population and world hunger. Political indifference to the clear-eyed science that has proven the dangers of human-caused global warming. The religious intolerance that is resulting in so many ghastly wars. The renewal of ethnic hatred, bringing about, among other things, threats to build actual walls against people different from one’s own. As core problems go, “political correctness” hardly competes with these.

To solve such real problems, we need a much larger commitment to education, rather than an abandoned one…public education in particular, supported much more fully by public funds than is now the case, so that those unable to attend private schools can still obtain a quality education…and excel.

The world will not be saved by engineers writing code. Rather, a well-educated public, conversant in the arts and hard sciences, the nature of soulful creativity and emotional intelligence, the history of civilizations, their literature and arts, will alleviate the difficulties we face and maybe even solve them.

Here, to be fair, is where training will come in handy. We’ll make good use of those handy tools like computers, the cloud and the internet, which in their usefulness take a prominent space in the same workbox, say, as the pencil.

Training results in workable solutions that get you through the day. It makes things more convenient…and otherwise is of little profound importance. There is almost no emotional intelligence in it, an element that, if you’re paying attention in school, a full education in the liberal arts and hard sciences provides in abundance.

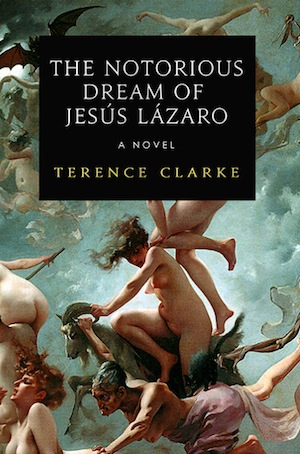

Terence Clarke’s story collection, New York, will be published later this year. This piece first appeared in Huffington Post.